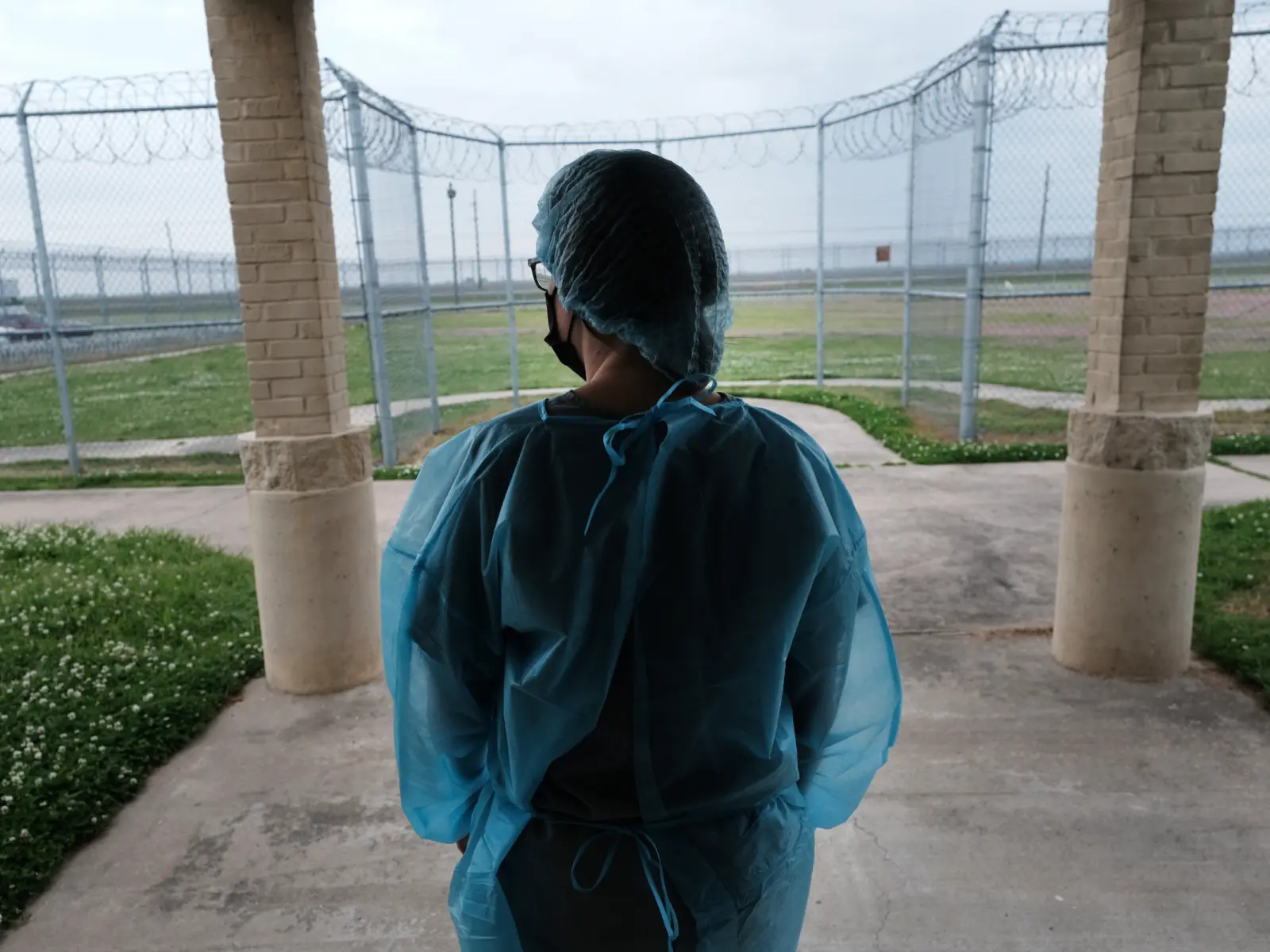

People returning to their communities after periods of incarceration often face major health challenges. Many struggle with substance use disorder and stand a high risk of overdose after their release. Chronic health conditions, including diabetes, infectious diseases, and mental illness, disproportionately afflict people who are incarcerated, leading to high rates of illness and mortality. And people often lack access to adequate health care before being incarcerated, inside of correctional facilities, and after they return home. The result is that they can cycle in and out of both the health care and criminal justice systems, at great detriment and cost to their wellbeing — and that of their communities.

To begin to address these issues, Arnold Ventures’ (AV) criminal justice team has made a commitment to work at the intersection of health care and reentry. A first and key partner in this emerging portfolio is the Health and Reentry Project (HARP), an initiative that aims to improve the health of people returning to communities after leaving prisons and jails. AV is supporting HARP to inform and accelerate federal policy changes in this area and to provide assistance to five states as they implement expanded access to Medicaid for people during reentry.

HARP’s work builds on research that shows significant benefits to community safety when people are able to access services and treatment upon release from incarceration. Access to Medicaid coverage, in particular, can reduce recidivism, and wider access to post-release mental health and substance use treatment can reduce crime overall.

We see strong interest among federal leaders, both Republicans and Democrats, in using Medicaid to help bolster public safety.Vikki Wachino founder and executive director of Health and Reentry Project

“As AV doubles down on evidence-based policy, expanding access to health care at reentry is an area of particular focus for us,” says Carson Whitelemons, director of criminal justice policy at AV. “The evidence base is strong, and scaling up change in this moment could have a major impact on improving people’s lives and increasing community safety at the same time.”

At a moment when federal policymakers have, for the first time, begun to allow Medicaid to cover services for people who are incarcerated, HARP is bringing together stakeholders from across the health care system, criminal justice system, and communities — many who have never worked together before — to design structures that meet justice-involved people’s health needs.

Vikki Wachino, founder and executive director of HARP, has dedicated her career to improving health care coverage, particularly in her role overseeing the Medicaid program at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the Obama Administration. She is also a former official at the White House Office of Management and Budget. We spoke to Wachino about how her deep experience with health care policy guides this essential goal in the context of reentry — and the powerful impact new federal policy could have.

This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Arnold Ventures

At a personal level, what brought you to this intersection of health care and reentry?

Vikki Wachino

I come to this from a health care system perspective. What motivates me to do this work is the opportunity to impact a group of people whose needs too often haven’t been met by the health care system. When I worked in the Obama administration, we extended coverage to millions of Americans through Medicaid expansion and launched some major delivery system reforms. Along with that, I had the chance to refresh federal policies specifically for people who are leaving prison and jail. But I left that role with some unfinished business. There was an opportunity to commit to meeting the health care needs of people in the justice system. My hope is that by bringing in my health care experience and working with criminal justice leaders, HARP can help transform care for this population.

Arnold Ventures

What’s the big health care and reentry policy problem that HARP is addressing?

Vikki Wachino

Access to health care before and after release from prison or jail has not been strong. Too often, people do not get the care that they need. This situation is coming back to bite us later when people show up to hospital emergency rooms with untreated illnesses. One reason for this is if a person is enrolled in Medicaid and they go into prison or jail, their Medicaid coverage turns off. When they’re released, they may not receive care until months or years later, and at that point they may have a lot of untreated health needs. Prison and jail officials are grappling with these unmet needs, particularly mental health and substance use disorders. Health care providers who work with people who are incarcerated are seeing big gaps in their ability to meet people’s needs, in part because there are so few connection points from the correctional system to the health care system, but also because we have not built services that work for people or earn their trust. We know that after people leave prison and jail they are 12 times more likely to die from common physical health conditions, like heart disease, and more than 100 times more likely to die of an opioid overdose than the general population. These are startling and frankly unacceptable outcomes for the health and justice systems. They drive high costs in public systems, as well as social costs. Because we’re not adequately treating people in the first place, they may end up needing a higher level of care. Also, they may end up in the justice system again, sometimes repeatedly. And all of this has a negative impact on crime and community safety. For all these reasons, we’re seeing more attention to this issue today.

Arnold Ventures

Tell me what’s so exciting about the recent federal policy changes around Medicaid.

Vikki Wachino

New Medicaid policies are allowing states to bridge the gap and connect people to health care before they leave prisons and jails, which helps them transition to community services after they return home. What’s groundbreaking is that, for the first time ever, Medicaid will pay for those services, both pre-release and post-release. Corrections departments and community providers will be able work together to provide people a basic set of services — case management, substance use treatment, mental health treatment, medications, and so on — while they’re inside. And after people are released, they’ll be able to access those services in the community immediately. The primary mechanism for doing this is what’s called a “Medicaid demonstration waiver,” a state-by-state process of experimenting with new designs in the Medicaid system to better achieve Medicaid’s goals. In April 2023, the federal government issued guidance on how states can use waivers to address these gaps in care at reentry. In the meantime, Congress has undertaken other incremental changes, authorizing Medicaid to cover services for young people during the pretrial period and at reentry. These changes apply in all states regardless of whether they have a waiver, and they go into effect next year. All this change holds enormous potential to achieve several different national goals — making safer communities, strengthening the health care system, and increasing racial equity, all while spending public money in a smarter way.

Arnold Ventures

What does the evidence say about the potential benefits of these policies?

Vikki Wachino

Historically, the modest efforts that have been made to connect people at risk of justice involvement with health care show promising results. One study looked at young men in South Carolina at high risk of justice involvement. Some lost Medicaid coverage when they turned 19, and some didn’t. The young men who retained Medicaid coverage were substantially less likely to be involved in the justice system, and the evidence strongly suggests that connecting people who needed it to mental health coverage in particular helped them to avoid justice involvement. Another study in Wisconsin looked specifically at the justice-involved population. It showed not only an overall increase in public safety but also a decrease in recidivism when people received Medicaid coverage. This all took place even before these new policy reforms, whose impact could be even more significant. We don’t know yet what the full range of impacts could be. For communities that implement this policy, maybe we’ll see high school or college graduation rates go up in 10 or 20 years. There are just so many potential downstream benefits that make evaluation of these policy changes really exciting in the long term.

Arnold Ventures

What work is HARP doing to support states in implementing the new waiver policies that allow Medicaid coverage?

Vikki Wachino

We have had an unprecedented groundswell of interest at the state level. Nineteen states are currently working on proposals or have had proposals approved, and more states are likely to join them. HARP’s challenge is how to translate these new Medicaid policies into a ground-level reality that improves people’s lives. It starts with bringing the health and justice systems together — health care leaders, state Medicaid directors, managed care organizations, service providers, sheriffs, state departments of corrections leaders, probation and parole officials, as well as victims of crime and people who have experienced incarceration — and helping them speak each other’s language. HARP is bringing these stakeholders together to discuss what each system needs, brings to the table, and should understand about each other. From there, they can tackle some really significant challenges, including both bringing Medicaid coverage into a correctional environment, where standards and resources vary a great deal, and successfully building a bridge that connects people to services after they’re released.

Arnold Ventures

What’s next as HARP moves forward in partnership with AV?

Vikki Wachino

The work that we’re undertaking with AV’s support is trying to advance progress on health and criminal justice issues in every state. We’re doing that through two new projects we’re launching with the National Academy of State Health Policy. One project is a learning and action network, which will help all states identify ways they can make progress in strengthening the connections between their health and criminal justice systems. That could include establishing stronger information sharing, or building networks of providers to work with people in the justice system. These are common sense steps that we’d like to see everywhere.

The other project is working intensively with five states with either approved or pending Medicaid reentry waivers, and helping them to implement the waivers in a way that makes meaningful improvements in people’s lives. In our policy brief Redesigning Reentry, we identified our North Star for doing all this work based on meeting with 70 stakeholders across the health and justice systems as well as advocates and people who are directly impacted. The North Star is a care model that connects people to primary care and behavioral health care with a strong focus on patient navigation, trauma informed approaches, and making connections to social services. Every person should have access to primary care, mental health and substance use treatment, connections to social services, and support in obtaining those services.

The interest in this policy among states is unprecedented. I’ve run the Medicaid program at the federal level, I’ve been following Medicaid waivers for a long time, and it’s unusual to see so many states volunteering to address these problems. As we make these groundbreaking changes, we’ll have a particular opportunity to build the evidence base of what’s effective and bring that to bear on future policymaking. That’s one value of the Medicaid waiver process, because there will be multiple states making varying implementation choices in parallel, but in different contexts. It opens up a big learning opportunity.

What’s been lacking until recently is policy attention, and we have that now. We see strong interest among federal leaders, both Republicans and Democrats, in using Medicaid to help bolster public safety. We see proposals being made by states with red governors and blue governors. We see a lot of interest from criminal justice officials. It’s a really exciting moment. Another big piece of our work is advancing federal policy reforms. We want to learn from these initial efforts and use what we learn to inform potential additional federal policy changes. And we’re excited to partner with AV on this, because of their historical commitment to the evidence base and track record of driving important policy changes in both criminal justice and in health care.