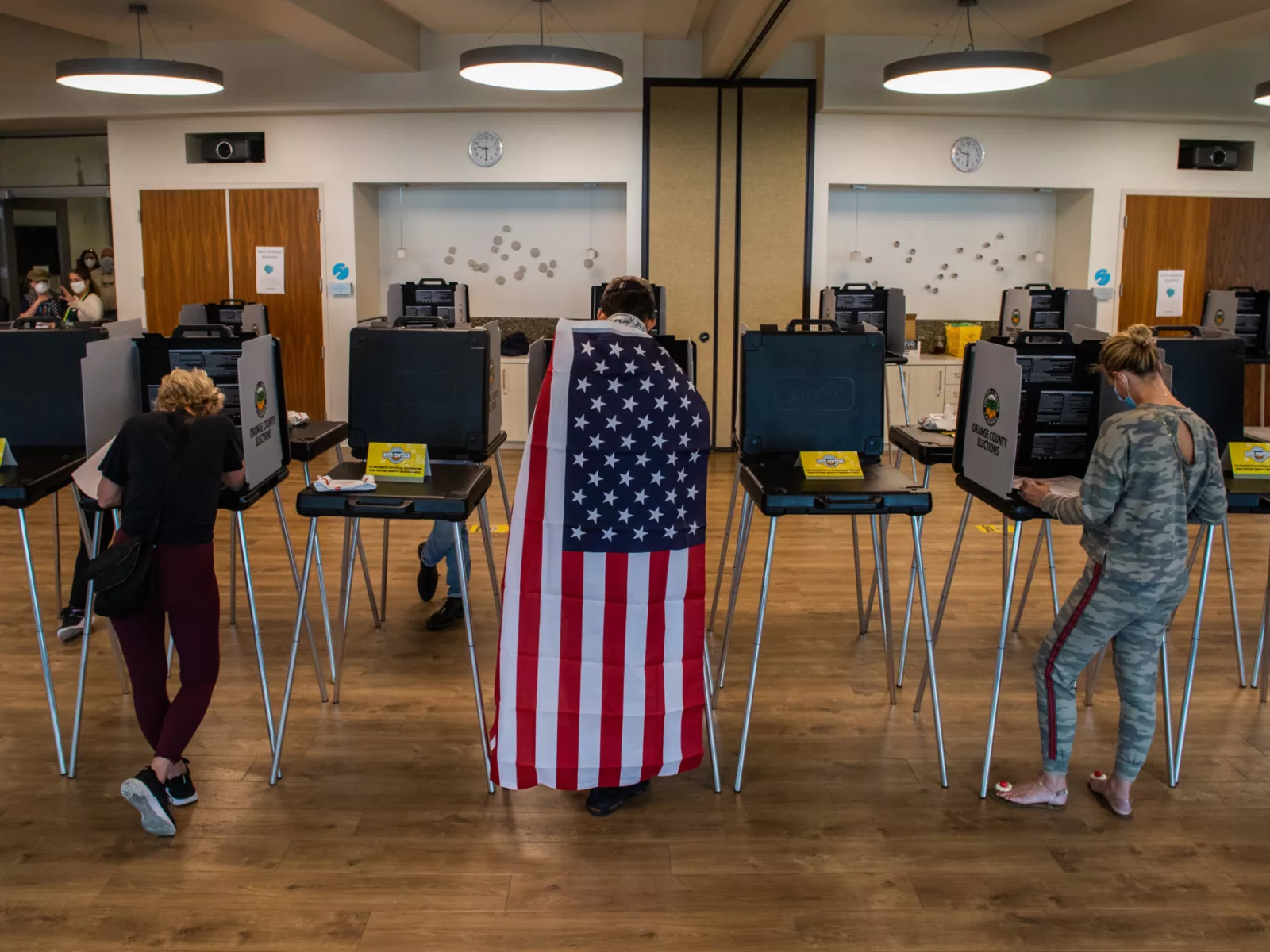

The number of cities using a voting method known as ranked-choice voting is set to double this year, to more than 50. Next year, Alaska will join Maine in using the method statewide. The idea is gaining traction, with cities including Denver, Washington, D.C., and King County (Seattle) considering adoption.

This kind of momentum may sound surprising to people who have heard of ranked-choice voting only through New York City’s recent mayoral primary. RCV received its fair share of negative press, the subject of late-night jokes and derision from national media outlets claiming it had sown confusion and led to delays in the outcome.

Such caricatures were misleading. The problems in New York had a lot more to do with the city’s patronage-plagued Board of Elections — which has been responsible for major blunders now for several election cycles in a row — than with ranked-choice voting. Other cities that use ranked-choice voting, including San Francisco, Oakland and Portland, Maine, manage to report results on election night. The decision by the NYC Board of Elections to delay the tabulation and release unofficial results weeks later, “had absolutely nothing to do with ranked-choice voting,” said Sam Mar, vice president of Arnold Ventures.

The experience in New York, in fact, demonstrated many of the advantages of using ranked-choice voting. Candidates responded to the new incentives to moderate their policies and diminish their attacks on one another, said Rob Richie, president of the nonpartisan organization FairVote. Turnout was up, while voters were left overwhelmingly satisfied with the process and its outcomes.

Contrary to the predictions of many critics, ranked-choice voting produced the most diverse election outcomes in NYC history. The number of women on the New York City Council is set to double, probably including an absolute majority of women of color. The city is almost certain to elect its second Black mayor in Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams, who emerged from the Democratic primary and will be heavily favored in November’s general election. “The claim that ranked-choice voting hurts minority voters is entirely without merit,” Mar said.

What Is Ranked-Choice Voting?

New York City voters approved a charter amendment in 2019 to adopt ranked-choice voting in local elections. It passed with 74% of the vote. Ranked-choice voting has usually won in recent years — mostly by a lot — wherever it’s been presented to voters as an option. Massachusetts voters did reject an RCV proposal last year, even as Alaska voters approved its use in future elections.

Ranked-choice voting systems differ by jurisdiction, but the fundamentals are consistent everywhere. Rather than picking a single candidate, voters rank their choices. In New York, voters could pick up to five favorites, in order of preference. If no candidate receives a majority of votes during the first count, the lowest-scoring candidate is eliminated, their support redistributed according to the second-place rankings, with the process continuing until someone does win majority support.

One way of looking at it is that ranked-choice voting acts as a kind of overall support rating. The winner of an RCV election has to be broadly acceptable to the majority of voters. In New York, Adams received 43% of the first-place votes but was ranked favorably by more than 60% of voters — as was the second-place finisher, former sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia. In 2013, Bill de Blasio won the Democratic primary with a comparable 40% of the vote but never consolidated broad public support; in fact, he is disdained by a broad cross-section of the city as he reaches the end of his two-term limit.

Nearly 1 million New Yorkers participated in the June primary — the second-highest total in the city’s history and double the turnout from four years ago. Ranked-choice voting is sometimes called instant-runoff voting and it indeed acted in that fashion, allowing voters to reach consensus without having to return to the polls (saving the city a projected $15 – 20 million expense in the process). When New York held a separate runoff election in 2013, turnout was just 6.9 %.

The number of cities using a voting method known as ranked-choice voting is set to double this year.

Critics of ranked-choice voting say it leads to “ballot exhaustion,” with voters unwilling or unable to name more than their first or perhaps second choices. In New York, 83% of voters ranked two or more candidates, according to exit polling. Further down the ballot, there was far less “dropoff,” with half the percentages of voters who voted for mayor but skipped the city comptroller and public advocate races than in 2013 — when former Gov. Eliot Spitzer was trying to stage a comeback as comptroller.

There were only two candidates in the Republican primary for New York City mayor, allowing talk-show host Curtis Sliwa to win with a simple (and sizable) majority. But Republicans did use ranked-choice voting in May to pick their nominee for governor of Virginia, businessman Glenn Youngkin, who prevailed in the sixth round.

The Virginia GOP field had been large and contentious, but the party has been able to rally around Youngkin. “It helped the party come together after a couple of the candidates were divisive,” said Richie of FairVote, which advocates for ranked-choice voting systems. “They feel very good about the ticket and how voters handled the system.”

Appealing Broadly to Voters

Exit polls showed that large majorities of New Yorkers felt comfortable using ranked-choice voting and support its continued use. Democratic voters were faced with a field of more than a dozen candidates, but most were ultimately satisfied with the two top finishers.

“Just as a mathematical matter, it is a better vehicle for translating the often-complicated preferences voters have,” said Kevin Kosar, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “The typical Republican and Democratic primaries tend to produce candidates who are more pleasing to the base, rather than most voters. Ranked-choice voting tends to override that tendency, producing candidates who are more liked by the population — and less disliked.”

Kosar said that’s what happened with Adams, who as a former police captain, was able to address voters’ growing concerns about crime. Garcia emerged as a surprisingly strong finisher, having held no previous elective office and winning praise mainly for her competence in running the city’s enormous sanitation and housing bureaucracies.

Garcia also benefited from an alliance with Andrew Yang, the former nonprofit executive who gained political celebrity with his presidential run last year. Yang had led in polls for most of the race but faltered at the end, ultimately finishing fourth. “Rank me No. 1 and then rank Kathryn Garcia No. 2,” Yang said at a Queens rally.

Ranked-choice voting saved the city a projected $15-20 million expense from runoffs.

Similar alliances were formed in New York City Council races this year and have happened elsewhere as well. Negative campaigning doesn’t go away under ranked-choice voting, of course, but mutually pursued destruction gives way to a more cooperative tone, with candidates less likely to castigate rivals for fear of alienating potential supporters. Instead of the usual punching up or punching down, forming a partnership becomes a real option.

Candidates, after all, have to win over voters who are scanning the entire field, not just picking a favorite and calling it a day that when they’re ranking up to five choices. “Adams is Brooklyn-based and won four boroughs,” Richie said, “but it made sense for him to campaign in Manhattan because every ranking matters.”

Such factors combine to create a more fluid environment than is traditionally the case. Other candidates aren’t as easily intimidated by early polling leads or massive campaign warchests, because they know they might go a long way as an acceptable second choice for many voters. And horse-race polling, which is often fraught, becomes more difficult under RCV’s multiple-choice format.

“Frequently in elections, one candidate jumps in with a ton or money or big name I.D. and other candidates decide they can’t beat this guy, so they don’t enter,” Kosar said. “Under a regular system, Andrew Yang could have run away with it.”

A Win for Diversity

The top four finishers in the mayoral race included three candidates of color and two women. Black voters were more likely to use all five of their choices than any other demographic group. “Many Black leaders expressed their fear that RCV would split the Black vote and that none of the Black candidates, of which there were several choices, would win,” wrote Maya Wiley, a civil rights attorney who finished third. “That didn’t happen, and the research shows that Black candidates who run against other Black candidates have higher win rates in RCV elections.”

In the Bronx, city council member Vanessa Gibson is likely to be elected in November as the first Black borough president, having gained support in later rankings from supporters of a Latino candidate who was eliminated but shared a similar platform, even though another Latino candidate was the second-place finisher. Queens Borough President Donovan Richards, who is Black, won the nomination, increasing his slim first-round lead over a white challenger by gaining support from a white progressive who was eliminated.

All told, more than 40 races in New York were decided by later rankings, not first-round majorities. The advent of ranked-choice voting in the nation’s largest city meant more voters came away pleased if not wholly delighted with their parties’ eventual nominees. “You want a candidate who meets the threshold of being broadly acceptable,” said AEI’s Kosar. “There is no perfect candidate out there because the definitions of perfect are so completely diverse.”