Eugenia Newby believes in the basic premise of democracy — that the majority should rule and that’s why we vote in the first place. Last year, Joe Biden lost her home state of North Carolina by a single percentage point, yet the Republicans who run the state legislature have recently approved a congressional map that all but guarantees their party 10 seats in Congress, compared with just three for Democrats, along with one seat that’s considered competitive.

Watching one party carve out such an unfair advantage for itself is why Newby, who works as a paralegal, is devoting a good portion of her free time volunteering for phone banks and texting campaigns, alerting fellow citizens about the abuses of gerrymandering and the risks it poses to other issues they may care about, such as school funding and Medicaid. “This is absolutely, positively wrong,” she said. “It seems like our democracy is slowly slipping away, especially with this gerrymandering that’s going on.”

Newby is not alone in her concerns. On Wednesday, the North Carolina Supreme Court delayed the state’s primary elections from March until May so that it can resolve lawsuits claiming that congressional and legislative maps are illegal gerrymanders that discriminate against Black voters. The action came two days after Attorney General Merrick Garland filed a lawsuit against new maps approved in Texas, alleging that they violate the Voting Rights Act and “deny or abridge the rights of Latino and Black voters.”

A Public Awakening

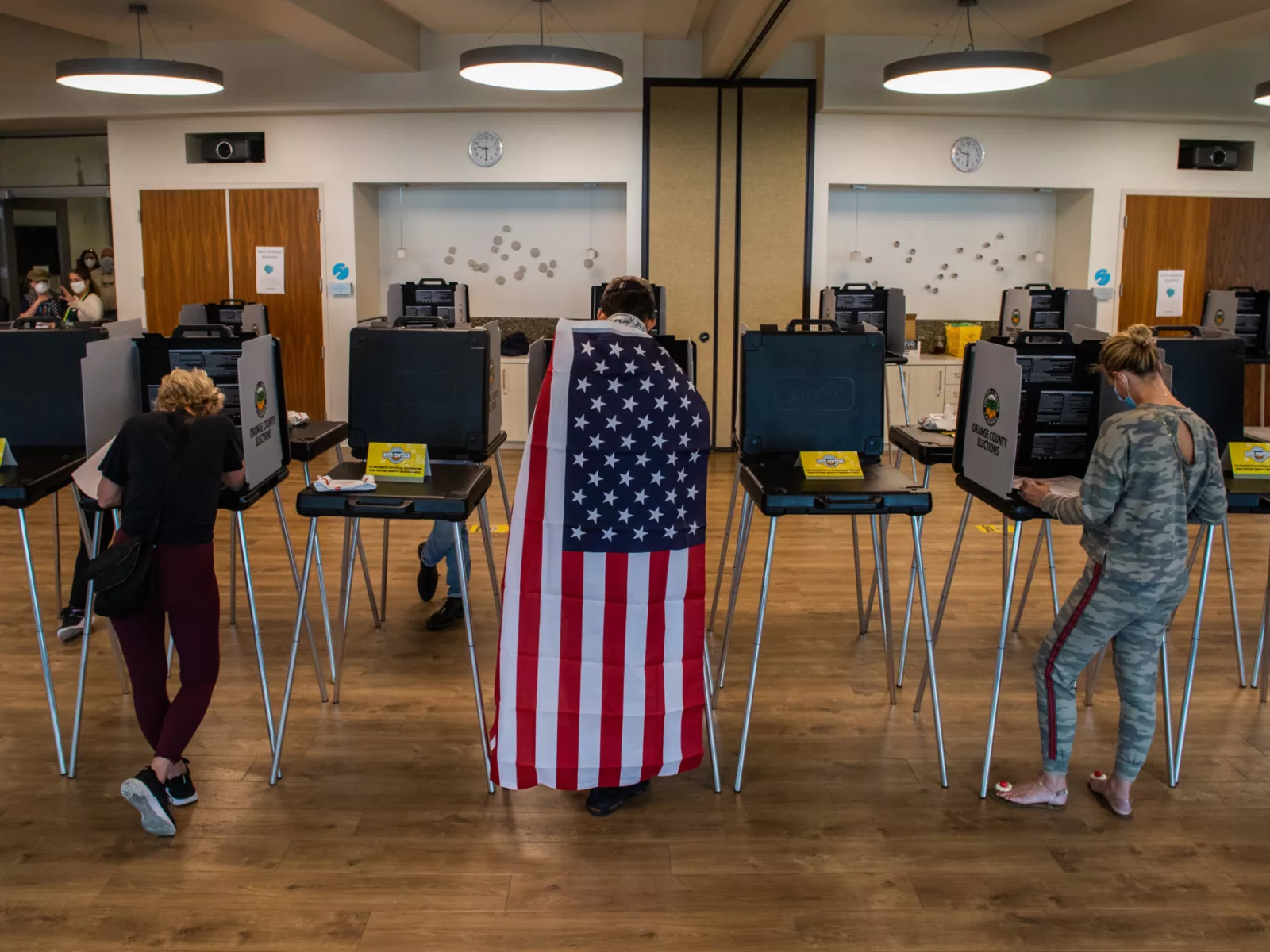

It doesn’t take career lawyers at the Justice Department to smell something fishy happening with many of this year’s redistricting plans. Across the country, more citizens are engaged in the redistricting process than ever before — lobbying, protesting, testifying and creating their own maps. They’re able to show what fair maps would look like — and issue specific criticisms of legislative proposals — thanks to the availability of far more powerful online tools than were available in previous decades.

“Public comment is more informed than it ever has been in the past,” said Moon Duchin, who directs the MGGG Redistricting Lab at Tufts University, which generates publicly-available mapping software. More than 5,000 communities have been mapped and uploaded for official comment using the lab’s Districtr tool, with thousands more generated on a weekly basis. Other groups have created mapping technology, such as the Campaign Legal Center’s PlanScore project. “The tools for drawing your own maps are easy and more accessible than they have ever been,” Duchin said.

It seems like our democracy is slowly slipping away, especially with this gerrymandering that’s going on.Eugenia Newby

On Wednesday, the GOP majority in the Pennsylvania House announced that it had chosen as its preferred congressional map a plan drawn by Amanda Holt, a redistricting activist who sued to block maps a decade ago. Holt, a former county commissioner, is a piano teacher and data consultant who used spreadsheets back in 2011 to challenge maps that split up local political jurisdictions but had far more powerful tools readily available to her this year. “It has a small GOP bias, but as far as non-commission maps go, it’s relatively fair,” tweeted Nathaniel Rakich, who covers redistricting for FiveThirtyEight.

Practically since the birth of Congress, redistricting has been used by parties to press their own advantages. The first politician known to be targeted was James Madison, whose district was larded with hostile Anti-Federalists by the Virginia legislature in 1788. Madison was elected nonetheless. The term gerrymander itself dates back to a corrupt Massachusetts map signed in 1812 by Gov. Elbridge Gerry.

But some of the most egregious gerrymanders in U.S. history have occurred just in the past decade. Congressional and state legislative lines are redrawn following each decennial census, along with numerous districts at the local level. Leading into the 2010 elections, the Republican State Leadership Committee ran a multi-million dollar campaign known as Project REDMAP in hopes of seizing power in the states — and in turn drawing safe districts for the party in Congress. The plan worked beautifully. In 2010, the GOP picked up 20 legislative chambers around the country — enough to dominate the process. They have controlled a majority of legislatures ever since.

Gerrymandering is now high on the list of problems that engaged citizens check off when they worry about the factors making partisan polarization worse and government less responsive. “For better or worse, the abuses of the redistricting process a decade ago has made more people aware of the problems,” said Adam Podowitz-Thomas, senior legal strategist for the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, which issues widely-cited grades for proposed maps across the country, assessing them for partisan fairness and other measures.

Independent Commissions

Democrats certainly manipulate mapmaking where they can, but Republicans simply control more states and have the final say over far more House seats. Despite tens of millions of dollars invested by Democratic donors in state legislative campaigns last year, especially through the National Democratic Redistricting Committee run by former Attorney General Eric Holder, Democrats failed to flip a single chamber last year.

Republicans currently control the political branches — governor plus legislature — meaning they control the redistricting process in states with 187 House seats, compared to 75 for Democrats. The congressional redistricting process has been completed in less than half the states, but it’s already clear that the number of competitive seats — already slim — will be further reduced with more districts drawn to be safe for one party or the other. “The whole thing feels so corrupted,” said Nancy Wang, executive director of Voters Not Politicians.

Her group led a successful ballot initiative campaign to take control of redistricting out of the hands of legislators and give it to an independent commission. The measure passed in Michigan in 2018 with 61% of the vote.

Around the country, the idea that voters should pick their politicians and not the other way around proved to be hugely resonant. It’s a process question that used to be considered strictly an insider’s game, but more citizens are aware of its importance — and sticking with a once-a-decade issue that takes extreme patience to address. “The public is paying attention and more are realizing how important redistricting is,” said Sean Soendker Nicholson, who ran the campaign behind a successful 2018 ballot initiative that put a nonpartisan demographer in charge of redistricting in Missouri. “You’ve got people who’ve been disgusted.”

Since the last round of redistricting, voters in states including Colorado, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Virginia, and Utah all approved measures either creating commissions or approving other methods to make redistricting less nakedly partisan. Just to compare two states under Democratic control, the congressional map generated by legislators in Illinois received grades of “F” from the Princeton Gerrymandering Project for partisan fairness, while the map created by Colorado’s new commission got an “A.”

Despite such clear expressions of public will, legislators have been loath to surrender power. In some states — including Missouri — they have put forward proposals that have directly undermined approved ballot measures. In others, they have hamstrung commissions by providing them with inadequate funding, or sniped at them from the sidelines with complaints that they’re excessively partisan. In some cases, organizers were not able to create truly independent commissions, leading to bodies that have been stacked with career politicians. In both Ohio and Virginia, such commissions failed to create maps at all.

In other states, there may be an independent commission, but the legislature is not bound to adopt its recommended maps. In 2018, Utah voters created a redistricting commission, but that new statute was easily amended by the GOP-controlled legislature, which voted nearly unanimously to gut key provisions such as a ban on incumbent protection. Instead, the legislature produced its own maps, ignoring the commission’s proposals. All four congressional districts were given a chunk of Salt Lake County, dividing and thus diluting the state’s main trove of Democratic votes. Similarly splitting of urban jurisdictions has taken place this year in other states including Arkansas and Ohio. “Unfortunately, we saw lawmakers turn their back on the commission and the maps are worse than they were 10 years ago, like so much of the country,” said Katie Wright, executive director of Better Boundaries, which sponsored the 2018 measure.

The Possibility of Federal Action

Despite the disappointments, redistricting reformers have not given up hope. For one thing, there’s still a possibility that Congress will set national standards. In March, the House approved a sweeping election bill that would have required all states to set up independent commissions. That proposal was later blocked by Senate Republicans. A later version would have required maps generated by states to meet minimal standards of fairness using various criteria for measuring partisan bias. That bill also failed, but sponsors say there’s still a chance that a limited filibuster carve-out will allow redistricting legislation to pass through the Senate.

One clever protest campaign run by the anti-corruption organization RepresentUs has been illustrating seemingly arbitrary lines by giving out free pizzas to people who live within badly gerrymandered districts, but denying slices to their nearby neighbors who reside just outside.

At this point, congressional action will come too late to affect the process in many states, but it would still lay the groundwork not only for future decades but court challenges against current maps. Litigation is a constant when it comes to redistricting. In 2019, the Supreme Court held that redistricting is an inherently political process, meaning there was no way for federal courts to set any standard to determine whether a gerrymander is unconstitutionally partisan. Back in the 1960s, Justice Potter Stewart offered a simple definition of pornography that quickly became famous: “I know it when I see it.” For his successors, the reverse is true of redistricting. Everyone understands when a map is drawn to favor one party or the other. But Potter’s successors have decided there’s no legal way to define when a partisan gerrymander violates the constitution.

Nevertheless, the supreme courts of North Carolina and Pennsylvania have both found that partisan gerrymanders violated state constitutional guarantees of free and fair elections. Thirty states have free, fair and equal election clauses in their constitutions, all but guaranteeing numerous challenges against maps in state courts.

“Even in states that will be heavily gerrymandered, the benefits of citizens participating is that it leaves a bread crumb trail for future litigation,” said Sam Mar, vice president of Arnold Ventures. “Showing that alternative maps were submitted by citizens concerned ahout racial or other gerrymandering builds the evidence base for courts later on.”

Racial Gerrymandering

Aside from concerns about partisanship and competitiveness, mapmakers have to keep in mind Voting Rights Act requirements for adequate minority representation, which is the basis for the Justice Department’s lawsuit against Texas. Legislators aren’t supposed to discriminate on a racial basis — but many continue to do so.

Usually, they are most concerned with advancing their own parties’ interest, protecting current incumbents or — in the case of many state lawmakers — carving out congressional districts that can advance their own careers. One clever protest campaign run by the anti-corruption organization RepresentUs has been illustrating seemingly arbitrary lines by giving out free pizzas to people who live within badly gerrymandered districts, but denying slices to their nearby neighbors who reside just outside.

All of this leaves voters frustrated. Districts that essentially guarantee election for either party means many politicians aren’t accountable to voters, or only to voters in primaries. Primary voters tend to be among the most ideologically partisan. Others may feel shunted aside — particularly independents, who aren’t allowed to vote in party primaries at all in 10 states. Lack of competition in both primary and general elections effectively disenfranchises millions of voters — if not in fact a majority. In 2020, just 10 percent of voters nationwide participated in party primaries that determined the outcome for the 83% of all House seats considered non-competitive.

That’s why gerrymandering has become such a pressing concern among those who feel like the whole game is rigged. “To have the public so engaged and aware and so outraged,” Wright said, “is a step up from people not even being aware of why redistricting matters.”