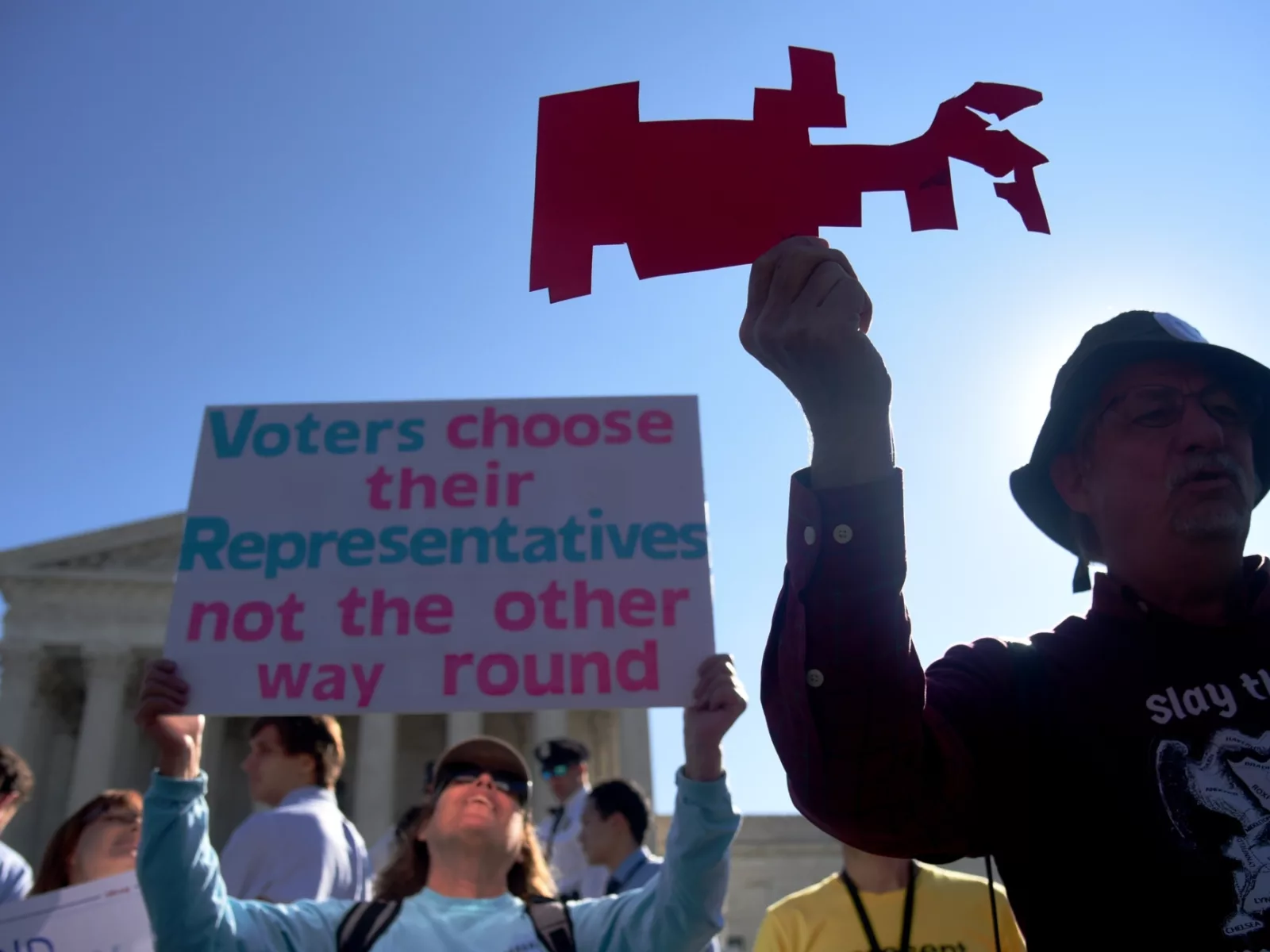

A surge of support for redistricting reform came after the last election cycle saw some of the most extreme gerrymanders in modern history. Lawmakers alike used sophisticated modern software to slice and dice voters more effectively than ever: In states as geographically diverse as Texas, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Florida, they drew maps that massively advantaged their own party, making it all but impossible for their opponents to gain a majority — no matter their share of the vote.

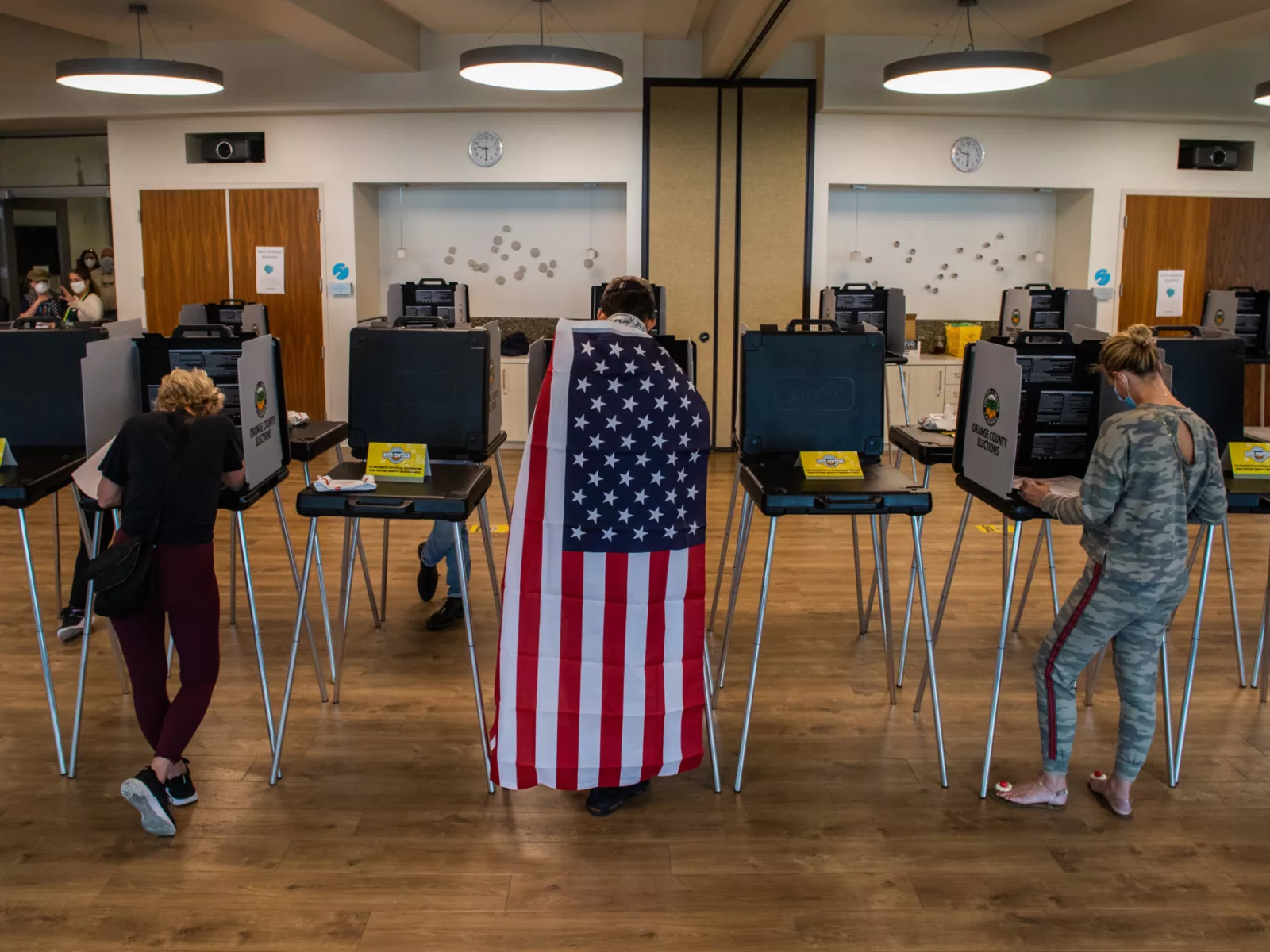

This Election Day, the outcomes of two ballot measures will determine how two more states are drawing their legislative lines. As voters head to the polls in Missouri and Virginia, the states face starkly different choices.

In recent years, Missouri’s elections haven’t allowed voters much of a role in picking their representatives. State lawmakers in power have used their control of the redistricting process to gerrymander legislative maps, reducing competition and all but guaranteeing they’ll be re-elected.

As a result, fewer than 10 percent of legislative races over the last decade have been decided by less than 10 points. And in half of all races, one of the two major parties hasn’t fielded a candidate at all.

“Everything is pre-baked,” said Sean Nicholson, Campaign Director for Clean Missouri, an anti-gerrymandering advocacy group supported by Arnold Ventures. “There’s no way to hold your elected officials accountable. And there’s no way to have a functional choice about who represents you.”

There’s no way to hold your elected officials accountable. And there’s no way to have a functional choice about who represents you.Sean Nicholson Campaign Director for Clean Missouri

In 2018, Missouri voters decided there was a better way. By a nearly 2 – 1 margin, they approved a ballot initiative spearheaded by Clean Missouri, which created a fair process by reducing the power of legislators over map-drawing and increasing transparency, among other steps. In a sign of the broad nature of support for the initiative, the Clean Missouri Amendment won majorities in every Senate district in the state.

But there was little time to celebrate. Not long after the Legislature reconvened in 2019, lawmakers began plotting their response. They ultimately referred their own ballot measure, Amendment 3, which, if approved by voters this fall, would not just undo the 2018 reform, but create a process even more rigged than the one in place. In response, Clean Missouri has launched a new campaign, urging a No vote on Amendment 3.

In Virginia, Giving Power to the People

The Show Me state isn’t the only place where fair maps will be on the ballot this fall. In Virginia, which saw an extreme partisan gerrymander last cycle, voters will weigh in on an initiative, Amendment 1, that would end legislators’ exclusive control of the process, giving ordinary citizens a major role. Fair Maps Virginia, another Arnold Ventures grantee, is leading the campaign for a Yes vote.

The moves in past years haven’t been just about strengthening parties. Many maps, like Missouri’s, were intentionally created to protect individual incumbents by creating very few competitive districts, denying voters a genuine choice among candidates. Several maps discriminated against candidates of color by diluting their voting power. And many maps were drawn behind closed doors, preventing voters from seeing the manipulation.

But the recent extreme gerrymanders sparked grassroots support for change. In 2018, in addition to the Missouri initiative, voters approved ballot measures to create fair maps in Colorado, Michigan, and Utah — a historic set of wins for citizen-driven election reform.

In 2020, the spotlight shifts to Missouri and Virginia. Though framed as another reform, Missouri’s legislator-backed Amendment 3 would scrap the nonpartisan demographer established by the Clean Missouri Amendment, putting lawmakers back in the driver’s seat for drawing maps. It also would explicitly allow partisan gerrymanders, and would kill Clean Missouri’s strong transparency provision and protections for minorities. It would make it all but impossible to challenge gerrymanders in the courts. And, perhaps most egregiously, it would make Missouri the first state in the nation to draw maps based on the number of eligible voters, rather than total population, a change which would reduce the power of urban and non-white communities.

“What they’re trying to do is unlike anything else in the United States, and certainly unlike anything Missouri has ever seen,” said Nicholson of Clean Missouri. “It’s really a trifecta of terrible ideas.”

Virginia’s ballot measure came in response to the gerrymander conducted by legislators last time around, which was a bipartisan affair — engineered in the Senate by Democrats and in the House of Delegates by both parties. The goal of that gerrymander was to protect incumbents of both parties. But the House map also turned out to give a major advantage to Republicans over Democrats, all but ensuring the GOP retained control, and rendering the will of voters nearly meaningless. Consider this: In 2017, Democrats won the total statewide vote by nearly 10 points — a whopping margin by historical standards — yet Republicans still came away with a majority of seats. This time around, Democrats have trifecta control in Virginia, and many are yearning for their turn to have the pen and exact revenge. If Amendment 1 passes, that power will instead be transferred from the legislature to an independent commission.

Brian Cannon, the Executive Director of Fair Maps Virginia, said activists have been working since 2015 to educate Virginians on the issue — including by sending volunteers to stand outside the polls on Election Day and engage voters in conversations about the need for redistricting reform. That’s allowed the campaign to expand its list of supporters from 35,000 to 120,000.

The measure on the ballot this fall would create a redistricting commission made up of 16 members — four legislators and four citizens from each party. Support from six of the eight citizens and six of the eight legislators — meaning at least four members of each party — would be required to pass a map, which would then also need to be approved by the legislature as a backstop. The measure also contains strong transparency rules, making it harder to manipulate the process behind closed doors.

A More Responsive System

If the fight against gerrymandering succeeds in Virginia, Missouri, and elsewhere, the benefit won’t just be a fairer-looking process in the abstract. If lawmakers no longer feel assured of re-election, they’re likely to be more responsive to the needs of their constituents. That should give a boost to other urgent and popular priorities for voters, from expanding health care access to fixing our broken criminal justice system to fighting climate change.

“Our work in support of democracy reforms was born out of a frustration with our dysfunctional and increasingly polarized political system, where even common-sense, widely supported reforms are unable to gain support or passage,” said Sam Mar, Arnold Ventures Vice President, Office of the Co-Chairs. “As we dug in to the issue, we realized that one of the root causes was our system of gerrymandering, which results in politicians who are no longer responsive to their constituents’ needs because they sit in a safe seat with zero accountability.”

“Ultimately,” Mar continued, “We believe that addressing the underlying root problems of our democracy will lead to a government that does a better job of solving problems for everyday Americans.”