Ivan Rivera was a young father working at the front desk of a self-storage company in the south Bronx when a sickening assignment came his way.

Someone had defecated on the steps outside. The janitor refused to clean it up. It was Rivera’s problem to fix.

“And it hit me,” Rivera said recently. “I’m making $9.50 an hour, and this is what I’m dealing with?”

He knew he had to do something different. By chance he saw a notification about a free job training program as he was cleaning out his email spam folder. He thought it was a scam — the offer sounded almost too good to be true.

It was no scam. Seven years later, in February of this year, Rivera took a new job as Vice President of Cloud and Application Vulnerability Management at financial giant Citi. He’s one of 6,500 New Yorkers and 10,000 students nationally who’ve completed a free four-month program at a nonprofit training center called Per Scholas, which has been preparing area residents for new careers since 1995. More recently, Per Scholas has expanded into 11 other cities around the country.

The program is designed to vault low-income workers into the middle class, turning $9.50-an-hour workers into well-paid tech industry workers with a career and a bright future. Job training programs are notoriously hit-and-miss, but Per Scholas’ has a demonstrated track record of making a difference.

“There are 6,500 proof points that this is working,” beams Abe Mendez, who runs the Per Scholas New York facility.

Mendez has more than anecdotes to back up that claim. Findings of a randomized controlled trial published March 12 show that Per Scholas graduates dramatically out-earn their peers, and the effect is long-lasting. Roughly, six years after completing the program, the average graduate earns 20% more than workers in a control group, the research found. This year’s results extend findings released in 2017 that showed Per Scholas graduates out-earned peers by more than 20% after three years in the job market. The new results also confirm findings from an independently conducted randomized controlled trial released in 2010 that found a similar earnings increase after two years.

Such rigorous scientific findings, reproduced across different studies, are hard to come by in social justice programs, and they suggest Per Scholas’ techniques can be replicated on a wider scale.

“We have the model here in place. It works. We know it can scale,” Mendez said.

The Per Scholas Bronx location has nine classrooms and meeting spaces that sit inconspicuously across the street from the famous Sabrett Hot Dog processing plant in an industrial area on the eastern side of the South Bronx. Overhead, the Brunkner Expressway soars over the South Bronx, carrying thousands of drivers each day away from New York City towards the leafy suburbs of southern New England. Underneath the elevated highway, amidst its near-constant rumble, Per Scholas classrooms offer unemployed or underemployed students a toll-free expressway to a better future. Roughly nine out of 10 students are members of a minority group, and a majority have only a high school or high school equivalency degree. Per Scholas courses prepare them for careers in technology, and more recently, cybersecurity, a field where the expressway is wide open. Experts predict there will be 3.5 million unfilled cybersecurity jobs worldwide by 2021.

Per Scholas has roots reaching back to the late ’90s, when early students were trained in computer repairs, and the nonprofit donated the repaired machines to schools and libraries. More recently, the organization has dramatically expanded, doubling the number of students in New York City since 2015 to 750 this year and adding facilities in Brooklyn and Newark, N.J. Nationwide, the organization has tripled enrollment since 2015 to 2,000 students this year, and now offers training at locations in Washington D.C., Columbus, Dallas, and seven other cities. Cost to provide the free program is about $7,000 per student, Per Scholas says, and depends on the training track and location. The organization recently announced a $31 million growth capital campaign.

“There is a critical need for programs that are truly effective, that enable people to train or retrain and lead them into jobs and that get them into the middle class,” said Jon Baron, Vice President of Evidence-Based Policy at Arnold Ventures, which is helping fund expansion of Per Scholas programs around the country, coupled with additional research trials to test and hopefully confirm that the earnings effects hold up in other settings outside the Bronx. Other donors include Ballmer Group and The Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation. “Per Scholas is exceptional in the quality of the evidence showing large, sustained effects on earnings.”

We have the model here in place. It works. We know it can scale.Abe Mendez Managing Director of the Per Scholas New York facility

The Per Scholas program is demanding. Students must attend class eight hours a day for at least 15 weeks. There is a strict dress code, and they’re expected to do three hours of homework each evening.

The promise of a better life keeps them going. In New York alone, Per Scholas placed 450 graduates into tech jobs at organizations like Barclays and Bank of America during 2019. In New York, students arrive at the school earning an average of $19,000 a year, and at graduation, last year’s group earned about $20 an hour to start, double what they came in earning. But more importantly, the program gives graduates a chance at a long-term career.

“Per Scholas doesn’t give you a dream job right away but what it does is it gives you a platform to begin with, that new fresh starting point in a career where you can progress quickly,” Rivera said.

Nathaniel Stovall, 28, from Harlem, came to Per Scholas after years of working in retail, and more recently as a purchase order coordinator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He said landing in a Per Scholas class was “intense.”

“Coming in, it was like learning a second language. Like learning Spanish, but you only have a couple weeks to learn it,” Stovall said. “But overall you get used to it, and after a while everything starts making sense.”

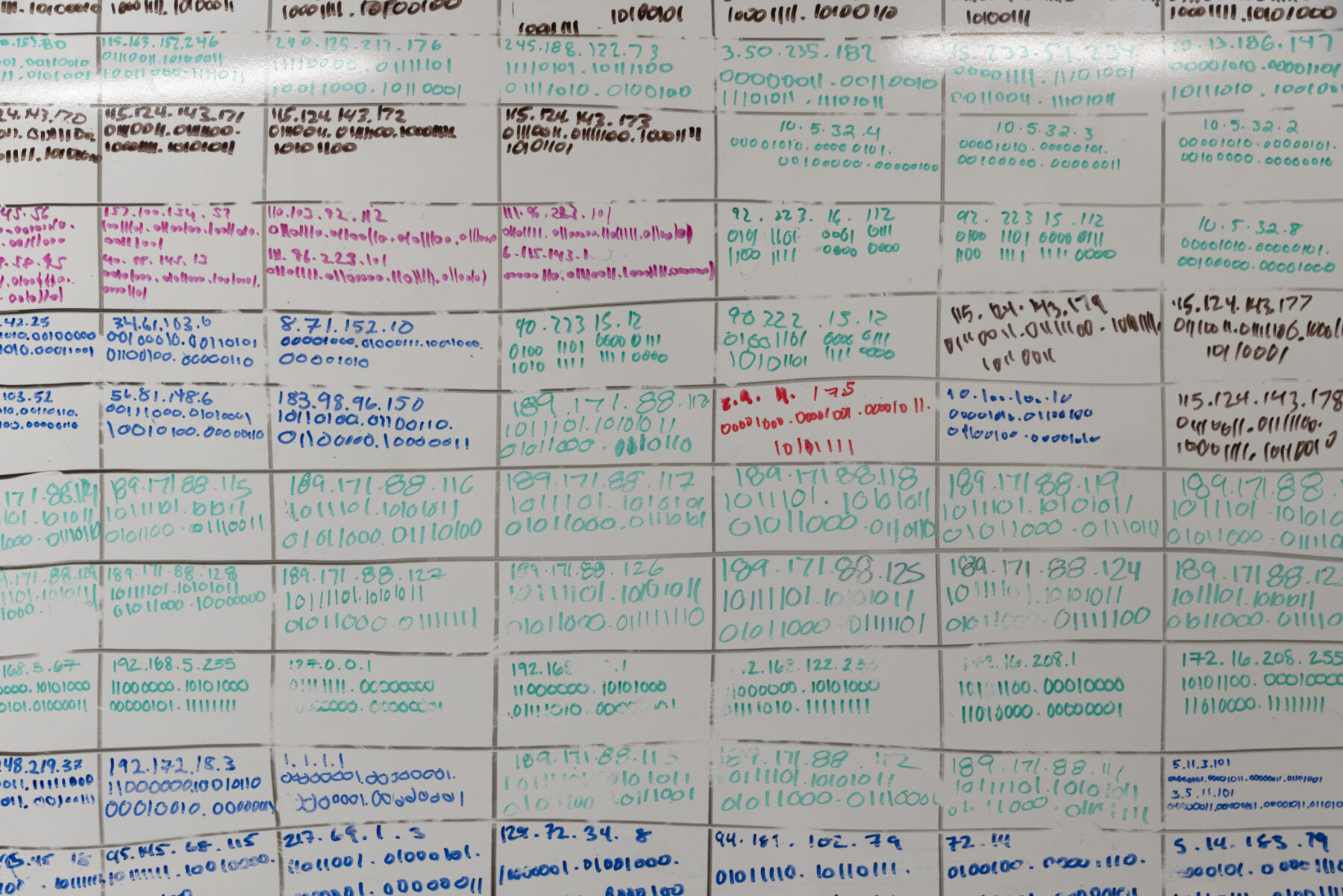

Things start snapping into place in part because of Per Scholas’ unique combination of hands-on technical training — one classroom is full of server racks and network switches — and a nurturing, holistic environment. In the Washington, D.C.-area classroom building, Per Scholas partnered with a food bank to offer free breakfast and lunch to students, said local Managing Director Joy King.

“Part of the interview process is to really understand and figure out what are all of the barriers a student might experience, so we can have an honest conversation about it,” King said. “We try to take that pressure away.”

Mendez, in New York, said the organization goes to great lengths to make sure students who are accepted can complete the program. Though working isn’t ideal while enrolled, many have tricky family situations — supporting extended families, for example. And some even work overnight shifts so they can enroll.

“We understand our students face lots of challenges,” Mendez said. “There’s food insecurity. There’s housing insecurity. There’s childcare issues. … We have emergency funding in the event a student is kicked out of their housing and are at risk of not completing program. We can jump in and support.”

Rivera said when he went through the program, Per Scholas would even help students who didn’t have professional clothes to wear to class.

“There’s a box in the back with ties,” he said. “They’ll teach you how to tie a tie if you need that.”

Per Scholas also refers students to outside organizations like Career Gear for help with professional attire as part of their student experience team.

“We sit down with each student now during their first week of training to get a clear picture on how we can support them from training to job placement,” Mendez said.

Mendez came to Per Scholas in 2019 from Barclays, the investment bank and financial services company, where he had spent four years overseeing community outreach programs, including Per Scholas. As an outsider, he was impressed by the program.

“What really sold me was I saw the community of Per Scholas graduates thriving at Barclays,” he said. He remembers recognizing a Per Scholas graduate who had trouble-shot his computer, as the IT worker on the cover of the Per Scholas annual report — and asked for his autograph.

In early 2019, Mendez accepted a job working at the nonprofit, and by the fall, he had taken the role of Managing Director of the New York office.

“I come from a background similar to our students. I grew up in the housing projects (in Harlem),” Mendez said. A child of immigrants, his parents were poor, but he attended Cristo Rey High School, which offered a workforce element — an internship at J.P. Morgan Chase — for all four years. He was able to turn that into a scholarship at Fordham, and a job at Chase, and later Barclays. “I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for that program.”

It’s no accident that Barclays was quick to warm to the Per Scholas model. Mendez worked in London for two years, where four-year college degrees are not always required of job applicants. In fact, U.K. firms pay an apprenticeship tax that’s used to fund such programs.

“It’s quite common to interact with colleagues who went straight from (the U.K. equivalent of) high school to an apprenticeship,” he said.

The apprentice model translates well to the United States with help from Per Scholas, which prides itself on “industry-led” design of its training courses. Mendez said the organization stays in constant contact with firms to make sure students graduate with skills that immediately translate into open positions; courses can be adapted within weeks when things change at the speed of tech. Another arm of Per Scholas actually does for-hire training and re-training that’s contracted by specific companies.

The model is working well for Alexis Mejia, 26, who grew up in East New York, Brooklyn. Mejia had been repairing cars as an auto technician since he was 14 years old, but after a decade of that, he realized that cybersecurity held more promise. In late February, just a few days from completing his program, he showed up for class in a sharp navy blue suit with a bold yellow tie.

“I had a job interview today,” he announced. “It’s a great company with so many opportunities for people with not that much tech experience.” He declined to name the firm because he’s still job hunting.

Job training, and re-training, is not easy. Studies show that many organizations fail to produce lasting enhanced job prospects, for a host of reasons — they have restrictive funding that prevents creative solutions, they don’t have relationships with hiring managers, they are understaffed and can’t afford to hire the right experts.

Rivera tried another tech school before he went to Per Scholas and it didn’t work for him because “it felt like high school … it felt like a machine.”

Rivera said the key to Per Scholas’ success is more subtle.

“Look, tech is one of those fields where you can learn on your own … The field is free to anyone,” he said. “What’s difficult is the people aspect. I feel like what they teach you at Per Scholas is the soft skills. How to speak in corporate environments. How to dress. How to engage. You learn all this consciously and unconsciously the whole time you are there. “

King, in the D.C. area, has seen these kinds of transformations again and again.

“It’s amazing for me to watch,” she said. “I remember a married mom of four, she had always been interested in IT but because she had four kids, she couldn’t … but there came a time.

“She talks so much about the confidence that she gained through the program. She never had to present herself to people before, never had to give a 30-second pitch. To have opportunity to go to a company like Capital One and meet other professionals was huge for her.”

Of course, students and mid-career professionals can learn in multiple different environments. A cottage industry of boot-camp style tech training programs, such as New York’s Flatiron School, have emerged. Community Colleges and even four-year colleges are offering more tech training as well. King doesn’t see any of these programs as competitors.

“I think of them as partners. We can have greater impact if we start to pool resources,” King said. In 2018, Per Scholas New York partnered with Bronx Community College to offer a two-year associate’s degree that integrates Per Scholas programs.

This nimble approach is relevant as robotics and artificial intelligence automate more and more jobs. Schools, employers, and labor organizations will have to address this issue head-on.

“Companies are upskilling and retraining workers. We are positioned very nicely in that space,” King said. “More and more companies are realizing that’s necessary.”

The biggest challenge for Per Scholas right now, Mendez said, is getting more firms to take a second look at Per Scholas graduates and their non-traditional career path.

“Some companies require a four-year college degree. We are trying to advocate for different models,” he said. Generally, the hardest job is to get that first student in the door. After that, “We get rave reviews and they come back for more.

“I’ve seen it work. I see it work every single day,” Mendez said. “I see all the challenges our students face, and I see the tenacity they have to push through and persevere.”

The organization’s other big challenge is its own success. In 2019, there were 1,700 applications for about 500 spots in New York — a 30% acceptance rate. Similar acceptance rates exist at all Per Scholas sites around the country.

One promising possibility: sharing teachers remotely. One networking class attended by 20 students in the Bronx was being taught by a teacher in Dallas, via video, who was instructing another 20 students in Texas.

Success isn’t just about the money graduates earn, of course. Baron, who manages Arnold Ventures’ support of Per Scholas, points to a study of graduates that asked questions beyond salary and employment status.

“In one of the trials in the Bronx, they asked people, ‘What is your satisfaction with your life?’ It was a surprisingly large impact,” he said. The report found that two years after beginning Per Scholas, 65% in the student group reported themselves as satisfied versus 44% in the control group. “Ultimately, this is what you would want to see from any program.”

Rivera, who is now on the Per Scholas advisory program, has certainly undergone that transformation.

“Back in 2013, when I went to Per Scholas, (the teacher) asked the class an honest question: ‘What’s the biggest achievement you’ve had in life?’ … I told her I honestly didn’t really have anything,” he said. “The one thing I was proud of was me standing there ready to change my life. And, I did. In my first four or five years in my career I feel like I was already matching or ahead of people there for 15 years. And now, after seven years, I’m a vice president.”