Solving homicides is one of the more important duties for local law enforcement, yet clearance rates for these types of cases remain persistently low in many U.S cities — and getting worse. In fact, the homicide clearance rate actually fell from 61.4% in 2019 to 54.4% in 2020, according to a study by crime analyst Jeff Asher. And in cities with populations larger than 250,000, the homicide clearance rate fell from 57.6% to 47.3%. Understanding what factors promote effective police investigation and crime solving is key to improving effective policing. Unfortunately, as the national debate over criminal justice policy becomes increasingly partisan, the actual role of police in reducing crime has been oversimplified and — all too often — overlooked.

Recognizing the lack of knowledge about what leads to successful investigations combined with the reality of low clearance rates, Arnold Ventures partnered with the Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy (CEBCP) of George Mason University to conduct a review on the current state of empirical knowledge and to identify evidence gaps. CEBCP is known for advancing rigorous studies through research-practice collaborations, and serving as an informational and translational link to practitioners.

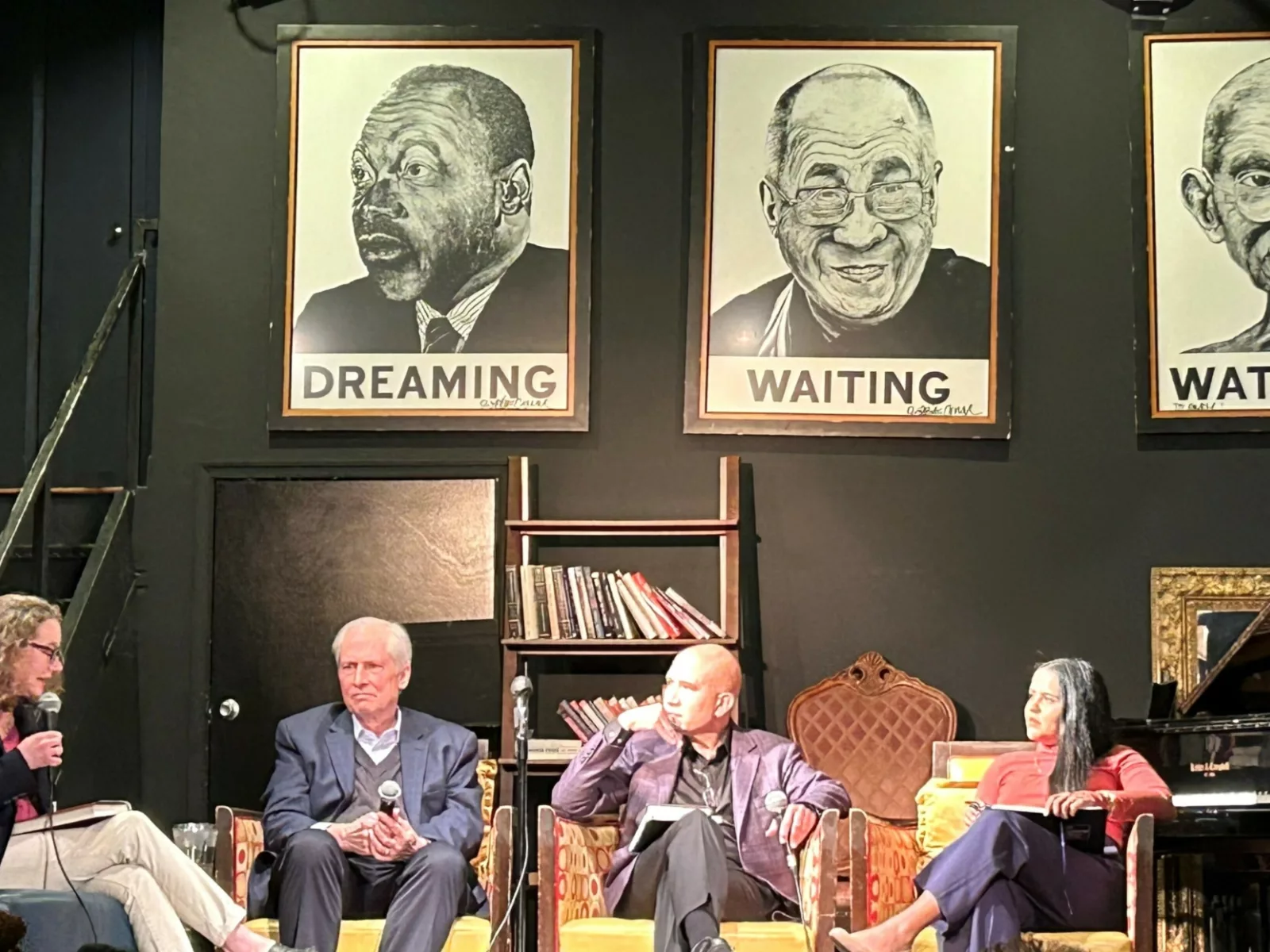

The CEBCP, led by Dr. Cynthia Lum, the director of the center, reviewed 79 studies on investigations conducted from 1975 to 2020 and published the findings in the report, Effective Police Investigative Practices: An Evidence-Assessment of the Research. These findings provided the framework for a workshop in October 2021, in which researchers, academics, and police practitioners — including Philadelphia Police Department Chief Inspector Frank Vanore and University of Maryland criminology professor Rod Brunson — convened to discuss and better understand the factors that drive clearance rates.

Arnold Ventures caught up with Lum, Brunson, and Vanore to hear their perspectives on the state of investigations at a time of rising homicides and persistent tensions between police and the communities they’re charged with protecting and serving.

Arnold Ventures

Cynthia, you co-authored the Effective Police Investigative Practices study, which looked at research on police investigations. Why did you take on this topic and what did you find?

Cynthia Lum

The goal was to map out what we know from existing research about effective investigations. The point was to not only mention that now there’s actually a great deal of research that looks at investigations and effective investigative strategies, but also some areas where we might need more knowledge in investigations. I think the bottom line is that the police can be effective in investigating criminal activity and, in many cases, linking that investigative activity to deterrence and prevention efforts. We now have a much better understanding about how investigators, detectives, and agencies can implement certain strategies that can be effective in improving clearance rates and solving crime.

Arnold Ventures

Why did you decide to hold the convening? What were some of the big takeaways?

Cynthia Lum

I think it’s important to bring what’s on paper to life. Doing so requires not only bringing the researchers in the room but also bringing in people who know investigations, who are the police practitioners, and who are living this reality every day. That link between the research and practice is so key to evidence based policing. It really is where the rubber meets the road. So the convening is intended to get the conversation started.

Arnold Ventures

Chief Inspector Vanore, how should we be thinking differently about police investigations?

Frank Vanore

I’ve been in investigations going all the way back to the early 1990s. A lot of what I learned back then was that you had to be able to get information from people, whether it’s interrogating the offender or getting a witness or family member to cooperate. But investigations have changed, and I think they’re changing for the better. Technology rules the day. Video, cell phone technology, social media — something as crazy as being able to track a car. Today, those are the factors that a good detective needs to look into when investigating a case. The answer sometimes isn’t at the crime scene, it’s going to be in the background.

Rod Brunson

I’ll add that we also have to consider the people’s lived experiences in communities impacted by violence, and what we hear is frustration. There’s frustration from detectives who can’t get the information necessary to help solve cases. And there’s frustration from community members who see known shooters and violent crime offenders walking around the neighborhood after they’ve committed crimes. Community members hold the police responsible for not doing their jobs. At the same time, the police hold the community responsible for not providing them the information that they need. A lot of my work helps to understand and to bring together those misunderstandings. Citizens have real world reasons for not coming forward to provide information. Maybe it’s fear of retaliation or things as relatively minor as having bad relationships with police officers. They see policing as trying to solicit information when it is to the police’s benefit, but the day-to-day interactions between police and communities are alienating and don’t necessarily garner support and cooperation.

Arnold Ventures

So is the struggle to increase clearance rates stemming from problems within police departments or is it something out in society?

Cynthia Lum

I think it’s important to understand there is no external or internal aspect of crime. Maybe some people might want to see policing and community as us-versus-them, but investigations and policing are all part of the fabric of the community. It requires a number of different groups working together towards a shared goal for crime rates to go down or for clearance rates to increase.

Rod Brunson

I want to ask something that’s probably controversial: Have we placed too much weight on clearance rates? Do clearance rates equate to a safer society? Do people feel that community violence is lessened with the fluctuation of clearance rates?

Frank Vanore

Any kind of statistics aren’t really a good measurement because anybody could do anything with statistics to prove their point. For people to feel safe, for people to trust the police, there has to be a change and that change has to be internal and external.

Cynthia Lum

I would add that we do have a number of ways that we measure things. None of them are perfect. But measures like crime rates or clearance rates can reflect how well we track certain things, how well we identify when harm happens, and improving on those measures is important. We do sometimes need measures to understand performance and to understand progress. There’s a whole ecosystem of policing within communities that contributes to crime rates, and clearances. So for example, Rod was mentioning the relationship between officers, that is, uniformed patrol officers, and the community. And there’s some research on this that indicates that that relationship, good or bad, can have impacts on whether or not people will talk to investigators or cooperate with prosecutors.

Arnold Ventures

So if communities are skeptical of police, but their involvement is key to closing cases, how can you lead them to want to help the police?

Rod Brunson

Police need to take any opportunity to engage with the community, and also to engage with third parties who can help bridge some of the divides. Those might be members of the clergy, people with prior criminal justice involvement, people who are acting as outreach workers or violence interrupters, and so on. You need all hands on deck. Anyone who’s willing to work in the interest of public safety should be invited to the table. That doesn’t mean it always has to be people who enthusiastically embrace the police. In fact, it might be people who have been critical of the police or haven’t been the best partners themselves to their communities.

Arnold Ventures

What else should police be doing to bridge that divide?

Frank Vanore

A lot of our problems began post-2014. We quickly saw after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, that people lost trust in the police. It took some real serious changes within our and other organizations, but we started to make some inroads again. We had people coming back to meetings. And then we lost that right around the death of George Floyd. As things began to settle down, we went into a pandemic and we were told not to go near anybody. It’s a little hard to build up trust when you’re doing a Zoom meeting.

Rod Brunson

It’s convenient for us to look at these flashpoints like Ferguson and the death of George Floyd, but I didn’t need Ferguson to tell me that there was a simmering hostility in communities toward the police. Race and policing is a historical, lingering, persistent problem in this country. We’ve yet to honestly and thoughtfully address it. It flares with each incident. It doesn’t go away.

Cynthia Lum

I would agree with both statements. Citizens have to believe that the police care about them. Sometimes that’s hard. I know this is going to sound like such an academic thing to say, but we don’t really have enough knowledge on what types of activities police can engage in to strengthen trust.

Rod Brunson

I’m sure some officers and agencies have great relationships with communities. And there are people in the communities who have great relationships with the police. But those relationships don’t permeate throughout those stakeholder groups. Police have more interactions with the community when they aren’t performing law enforcement functions. So those are opportunities to be less adversarial, and where genuine relationships can be formed.

Arnold Ventures

So what is the future of investigations?

Frank Vanore

Technology. For example, right now in Philadelphia we have a major carjacking issue, which I think we’re sharing with a lot of the country. But what I’ve learned is that every one of these cars, especially the newer cars, can be tracked. They’re like a moving cell phone. Things like video enhancement, cellphone enhancement, and social media will also help us solve crime way quicker. And ring cameras. It used to be that cameras were few and far between. Now you can’t go down the street without finding 10 houses that have some kind of video hooked up.

Rod Brunson

With the advancements in technology, there’s still a critical need for people who can get up on the witness stand and raise their hand and swear to testify. I’m sure that would aid prosecutors in being able to achieve their goals as well. So I think the combination of the technological advances, while continuing to work on old school, traditional shoe leather police work, will always be critical as well.

Cynthia Lum

I would say my response is more aspirational. We need more knowledge about the effectiveness of these technologies. We need to more precisely identify ways in which the police can engage with the communities that will lead to positive results, not just for investigations, but for relationships more generally. And it’s important to bring more transparency and accountability to the court system as well. Recognizing that investigations and police work exist in a broader ecosystem is important to keep the research moving forward.